Mitkadem Hebrew for Youth Ramah 06 Student Pack

- Blessings formula

- P'tichah/chatimah

- Chosen people

- Giving of the Torah

Mitkadem is a self-paced Hebrew prayer and ritual program designed to empower every child to learn Hebrew. Created with an understanding of the realities of supplementary Jewish education (limited time, inconsistent student attendance, different levels of Hebrew knowledge, levels of motivation, and involvement with Jewish practice), the Mitkadem program consists of 23 levels that introduce grammar, vocabulary, and reading. Students can work alone or practice reading with a partner.

How It Works:

The first two units (called "ramot") focus on developing decoding skills and ritual vocabulary. Ramot 1 and 2 are teacher-directed, with a combination of independent study and group work.

Ramah 3 introduces students to the Mitkadem system and to a self-paced, self-directed Hebrew learning program.

Ramot 4-23 cover a particular prayer or family of prayers that share a theme. Students complete each packet individually or in small groups. Students generally can complete between three and six packets per year. As students successfully complete a packet (and pass both an oral and written assessment), they advance to the next.

Benefits:

• Each student engages with the material at his or her own level and pace.

• Frees teacher time by eliminating class review of material for students who miss a lesson or learn at a slower pace.

• Students can pick up where they left off. No need for them to feel left behind or make self-conscious comparisons to their peers.

• Diminished behavior problems because students are occupied at their own level.

• Students cannot "fall through the cracks," because of constant monitoring and regular assessments.

Features:

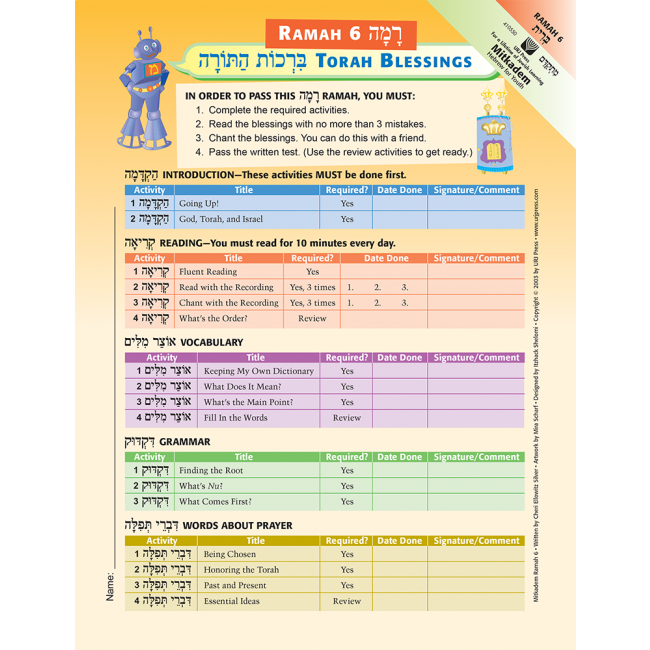

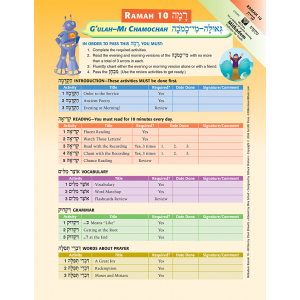

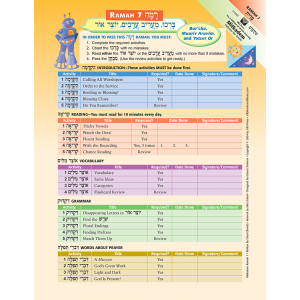

Different from traditional textbooks, every ramah includes several booklets with five categories of activities:

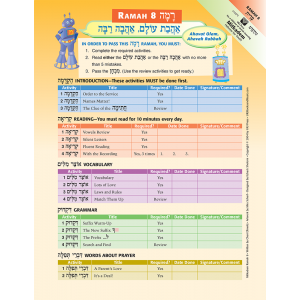

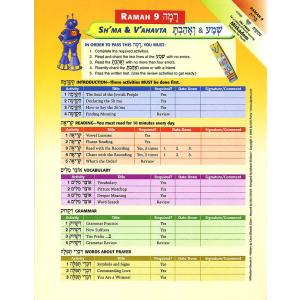

1. Hakdamah — Introductory activities that serve as an "advanced organizer" for the unit and must be completed before moving on.

2. K'riah — Reading activities that drill decoding skills, fluent reading of fluency, and if appropriate, chanting of the prayer.

3. Otzar Milim — Vocabulary activities drill key words and important phrases found in the prayer.

4. Dikduk — Grammar activities teach and have students use roots, prefixes, and suffixes found in the prayer.

5. Divrei T'filah — Activities emphasize concepts and critical thinking skills. In this section, students delve into the theological and philosophical ideology expressed in Jewish liturgy.

1. What is Mitkadem?

Mitkadem: Hebrew for Youth is an innovative, self-paced Hebrew prayer and ritual program designed to empower every child to learn Hebrew. Mitkadem was created with an understanding of the realities of supplementary Jewish education (e.g., limited time, inconsistent student attendance, different levels of Hebrew knowledge, different levels of motivation and involvement with Jewish practice) and is part of a comprehensive approach to Hebrew education.

The Mitkadem program consists of twenty-three Ramot (levels) that introduce letters and vowels, prayers from the worship service, Jewish concepts, basic grammar, and vocabulary. The first two Ramot develop reading skills and ritual vocabulary. Ramah 1 is a pre-primer, focusing on Hebrew reading readiness through letter recognition. Ramah 2 is a primer, teaching Hebrew letters, vowels, and the blending of letters and vowels to form syllables and words. Ramot 1 and 2 are teacher-directed, with a combination of independent study and group work, and can be completed in one or two years, depending on the school and the progress of each student. Ramot 1 and 2 are designed for students in grades 2–4 who are beginning Hebrew study. They are unique in that they begin to teach independent learning, the foundation of the upper Ramot.

Beginning with Ramah 3, Mitkadem becomes a self-paced, self-directed Hebrew learning program. Ramah 3 is the m’chinah or preparatory Ramah that introduces students to the Mitkadem system. Each subsequent Ramah covers a particular prayer or family of prayers that share a theme. As students successfully complete a Ramah (and pass both an oral and written test), they advance to the next. Rather than traditional textbooks, every Ramah includes a number of pamphlets with activities divided into five categories:

Hakdamah: Introductory activities that set the stage for the theme of each prayer and related activities. These activities serve as an “advanced organizer” for the unit and must be completed before moving on to the remaining activities.

K’riah: Reading activities that drill decoding skills, fluent reading of the prayer, and if appropriate, chanting of the prayer.

Otzar Milim: Vocabulary activities drill key words and important phrases found within the prayer.

Dikduk: Grammar activities teach and have students use roots, prefixes, and suffixes found within the prayer.

Divrei T’filah: The activities in “Words about Prayer” emphasize concepts and critical thinking skills. In this section, students delve into the theological and philosophical ideology expressed in Jewish liturgy.

The Ramot are designed for self-study, and students work through them at their own pace, individually or in small groups. The Mitkadem program is supported by a full range of teacher’s guides, audio CDs, and student manipulatives, as well a comprehensive network of professional and peer support.

2. What does a typical Mitkadem classroom look like?

Imagine a classroom filled with motivated students eager to delve into their work. As students enter the classroom, each retrieves his or her own folder, which contains the Ramah on which he or she is currently working, and picks up where he or she left off at the end of the previous session. There is a buzz of activity as students work individually or in small groups, sitting at tables or on the floor. Students choose which of the five different types of activities they wish to work on at any given time, but must complete them all before progressing to the next Ramah. Students may be writing, reading, listening to an audio recording, playing a game, or studying with a teen aide. Each is engaged with material that is appropriate for him or her. A sense of accomplishment and purpose directs their efforts. The teacher moves around the classroom, guiding and supporting, free to assist each child individually. As each student completes all of the activities in a particular Ramah, written and oral assessments are administered, and upon successful completion of the tests a student progresses to the next Ramah. During the last several minutes of each class, the teacher may choose to gather the students for a large-group closing activity, which may be a discussion, a game, group singing, or the recitation of a particular prayer.

This scenario describes one possible way of setting up a Mitkadem school, where students engage in the five different types of activities in a single classroom under the supervision of one teacher. There are other creative models, however, including a structure in which different types of activities take place in different classrooms under the supervision of different teachers. For example, Ms. Schwartz’s room may be the reading area, Ms. Levy’s room is the grammar and vocabulary location, and Mr. Cohen’s room is where the audio listening stations are set up. All students at any age or grade level would go to those locations when engaging in those specific activities. This model allows teachers with particular strengths to focus on those areas and promotes a larger “all-school” sense of community. It does, however, result in much more movement by students from classroom to classroom and requires teachers to deal with a larger number of individual students.

These are just two possibilities. The flexibility of the Mitkadem program allows each school to tailor the program to fit their particular circumstances and needs. No matter how the program is structured, though, Mitkadem allows students to feel that they are able to learn and be successful, regardless of their level of ability. Highly motivated and adept students speed ahead as they discover just how engaging and meaningful the study of Hebrew and prayer can be. Teachers quickly identify those students who, due to absences or learning issues, need special help. One-on-one attention and individually designed programs can accommodate these students as they continue to work productively alongside their classmates.

3. How does the testing process work?

Once a student has completed all of the activities in a Ramah, he or she must demonstrate understanding of the material and achievement of a certain level of competence before moving on to the next Ramah. Ideally, testing should be done in a quiet place—many schools designate a quiet, private classroom or office as the “testing room.” The testing includes both written and reading assessments and should be administered by a staff member who can help with questions and give immediate feedback on the student’s work and reading or chanting.

While many religious schools are not accustomed to administering written tests, they are an important component of the Mitkadem program. They let students and parents know that the school is serious about students’ learning and school accountability, and the test gives students something to work toward. The written tests are found in the Teacher’s Guide and are copied for students as needed. The oral assessment is accomplished by a tester listening to each student read and/or chant individually. Objectives in each Teacher’s Guide suggest a minimum level of reading fluency, but these guidelines can be adjusted or amended by each school to suit their own needs.

If a student successfully passes both the written and oral assessments, he or she is ready to move on to the next Ramah. The completed Ramah is sent home, and the completed test is placed in the student’s cumulative folder. He or she is then given the pamphlets of the new Ramah and sent back to class. Students who are determined to be deficient in one or more areas are sent back to the classroom to study or to work with the teacher on the areas of weakness. Of course, every student passes eventually, or they cannot progress in the program. For those students with learning issues, the written and oral assessments can be adjusted to include only specific items, or the way in which the test is administered can be adapted to suit any student’s specific needs. More detail on the testing procedure and suggested criteria for “passing” scores can be found in the Mitkadem Teacher’s Guide for Ramah 3 through 6 .

4. How much time does Mitkadem require?

In a setting that allows two hours of Hebrew study per week, the average student should complete three to five Ramot per school year. This would lead to completion of all twenty-three Ramot in five to six years (typically grades 2–7). Each Ramah will take from two to eight weeks to complete (Ramot are different lengths—some prayers are longer, some Ramot include more than one prayer, some schools spend more time on certain Ramot). Highly motivated students may complete six or seven Ramot in one year.

In recognition that schools vary widely in the amount of time allocated for Hebrew study, Mitkadem is structured to provide great flexibility in how it can be implemented. A school can choose to use the program in a number of ways:

-

Follow the program in its entirety, progressing from one Ramah to the next.

-

Pick and choose which Ramot are essential to your particular institution, and skip those that are not as important. (However, because Ramot progress in difficulty and depth, even when skipping, students should proceed in numeric order. Proficient students can always go back and complete Ramot previously skipped.)

-

Limit the number of Ramot or the number of activities within a particular Ramah for students who move more slowly. Choose the prayers or activities that are essential for them to cover.

-

For special-needs students, carefully select Ramot and activities, or modify activities.

5. What are the benefits of a self-paced approach?

The self-paced nature of Mitkadem allows each student to be involved and engaged with the material at his or her own level. This approach provides numerous benefits:

- There is no longer any need for a teacher to go back and cover material a second or third time because some students missed a lesson or because some students have not yet grasped the material.

- Motivated and knowledgeable students can proceed quickly through the material. They will feel a sense of accomplishment and understand that Jewish study can be challenging and stimulating.

- Students who have more difficulty with Hebrew and/or are absent frequently can pick up wherever they left off. They may not cover as much material as more proficient students, but they too will feel good about and grounded in what they do accomplish. They need not feel “left behind” or self-conscious when compared with their classmates.

- With all students occupied at their own level, behavior problems in the classroom diminish significantly.

- If a few students fall behind or want to progress more quickly, they can do work at home with no disadvantage to those students who do not do work at home.

- Students cannot “fall through the cracks.” With constant monitoring of work, it is clear if a student is falling behind, doesn’t understand material, or is reading below grade level.

6. What is the role of the teacher in a Mitkadem classroom?

With the Mitkadem program, the role of the teacher is not a traditional one. While frontal, whole-group lessons can close a session or occasionally replace a Mitkadem session, this approach is not the norm. The self-paced nature of the program enables the teacher to be a resource, facilitator, and coach for students’ individual, self-directed Hebrew learning. Rather than directly presenting material in a lecture-style format, a Mitkadem teacher will move around the classroom, monitoring, guiding, and assisting students as they work individually or in groups. The teacher is the nucleus of the classroom, managing students as they work at a variety of different paces and levels. The teacher maintains a functional system for working, keeping students on track, assessing student progress, and addressing individual needs.

Most teachers will require some training in order to comfortably run a Mitkadem classroom. We recommend that you contact your URJ Regional Educator to discuss training possibilities with you.

7. What is/should be the role of parents in Mitkadem?

Parents desire to be part of their children’s education on a variety of levels. Some simply want to be informed, some would like to help and guide their children’s learning, and some would even like to learn themselves. The Mitkadem structure offers opportunities for parents in all these ways:

Keep parents informed

Each time students complete a Ramah, teachers should send home the completed pamphlets. This will inform the parents that their child has moved on to a new level and show them what has been accomplished. One educator has developed a set of postcards that are mailed home to parents whenever a student completes a Ramah. The card congratulates parents on their child’s progress, indicates what material will be covered in the next Ramah, and provides room for the teacher to write individual comments. These postcards are available for download at http://urj.org/chai/tools.

Offer option for homework

Parents can choose to purchase a duplicate of each Ramah for home reinforcement of the work their students are doing in the classroom. Each time students begin a new Ramah, the school can arrange for them to receive a duplicate packet of pamphlets, copies of the answer sheets, and an audio recording to take home. This allows parents to see what their child is learning and provides an opportunity for parents to learn from the material themselves. A sample order sheet is provided on page 27 of the Mitkadem Teacher’s Guide for Ramot 3 through 6 .

Parents as aides

Parents can volunteer to assist in the classroom. Those who are knowledgeable can help students, tutor reading, and even serve as testers. Others can help students understand directions and perhaps check work against the answer sheets. The more help for the teacher, the better.

Parents as learners

The Mitkadem material is perfectly suited for intergenerational learning. Parents and children can learn alongside each other in the classroom, as well as at home.

8. Can children and parents learn together with Mitkadem ?

Yes! Mitkadem is being used very successfully in a number of intergenerational settings, where children and parents, as well as other adults who do not have children in the school, learn Hebrew together. The self-paced nature of the program and the possibilities for small group work are especially well suited for such a situation. Adults can be teamed with students in chevruta pairs that can work through the program together, both in the classroom and at home. This type of intergenerational learning program is a great way to involve parents in their children’s education, as well as in the school and the synagogue.

9. Can Mitkadem work in a small school without a large staff?

Absolutely—in fact, Mitkadem works particularly well in such settings. Many small schools have mixed-age classrooms (for example, third and fourth graders together in a single classroom). Mitkadem’s self-paced structure (at Ramah 3 and above) allows every child to work at his or her own pace and be engaged with material that is appropriate for his or her individual level of Hebrew. And, as explained above, Mitkadem works very well in multigenerational settings where children and adults learn Hebrew together. Because Mitkadem does not require that everyone be doing the same thing at the same time and at the same pace, it is very well-suited for a “one-room schoolhouse” type of setting.

10. How do we keep track of all the materials?

Establishing a good working system for keeping track of all the materials used in Mitkadem is very important. The program works best when one person is designated as the program administrator and assumes the primary responsibility for organizing and managing the program. This person can be the principal, the Hebrew coordinator, or a lead Hebrew teacher.

Each student should have his or her own pocket folder to hold the pamphlets of the Ramah in progress and other work materials. It is helpful for each class to have a uniform color folder, which remains “their” color throughout their years in Mitkadem . For example, when the fourth grade begins Ramah 3, all students receive a yellow folder. When they move into fifth grade, they retain the color yellow (though they will likely need new folders each year, because they wear out), and the new fourth graders each get a green folder.

Student folders will contain three items:

- The pamphlets of the Ramah currently in progress .

- The Prayer Map , a graphic representation of all of the Ramot in the order of the service. Located in the appendix of the Mitkadem Teacher’s Guide for Ramot 3 through 6 , the Prayer Map should be copied on card stock and kept in each student’s folder throughout the program. The Prayer Map designates evening and morning as well as Shabbat and weekday prayers. It can be a tool for students to keep track of what they have accomplished—when the student finishes a Ramah, the teacher can indicate its completion on the Prayer Map with a check mark or a sticker.

- Milon (Dictionary): In the B’rit pamphlet at the start of each new Ramah is a vocabulary list particular to that Ramah, called Milon Sheli (My Dictionary). One of the activities in each Ramah has students add those vocabulary words to their personal dictionaries, so their milon grows as they progress through the program. More information about options for how students can create their own milon can be found in the Mitkadem Teacher’s Guide for Ramot 3 through 6 .

Student folders should not leave the classroom, but should be kept in a location that is easily accessible so that students can retrieve their own folder and begin working independently or in a small group as soon as they enter the classroom. If homework is necessary or desirable, parents can purchase a duplicate of each Ramah for their child to work on at home. See below for more on homework.

As you become familiar with the design of the student packets, you’ll notice that the last several pamphlets in each Ramah contain answer sheets for some or all of the activities. Having access to these answer sheets allows the students to get immediate feedback to their work and will eliminate a lot of the time it would take the teacher to check each worksheet for correct answers. Some schools include the answer sheets with the material given to students at the start of a Ramah; others give them to students only when the teacher verifies that the student has completed the worksheet and is ready to self-check. Whichever method you choose, students will quickly learn that “cheating” doesn’t help—if they have not legitimately completed all the work they won’t be able to pass the test at the end. Self-checking is an important component of the Mitkadem methodology.

11. How do we track student progress?

The program administrator will also need to maintain a cumulative folder for each student, containing a record of his or her progress through the Mitkadem program. Cumulative folders can be kept in alphabetical order by class and stored in a file cabinet in the principal’s or program administrator’s office. In the Appendix of the Mitkadem Teacher’s Guide for Ramot 3 through 6 is a template for a cumulative record that can be copied onto card stock and placed into each student’s cumulative folder. When students pass a test, the accomplishment is recorded in their cumulative file, and the completed test is filed as well. The color of a student’s cumulative folder can correspond to the color of his or her class folder, helping identify students by grade.

A Hebrew Progress Report can be used once a month to help teachers reflect on the progress of each student. Since lesson plans are not necessary with the Mitkadem program, this form helps the principal or program administrator stay informed of class advancement. A template is provided in the Appendix of the Mitkadem Teacher’s Guide for Ramot 3 through 6 .

To have an instant view of how a class as a whole is progressing, you can create class charts for each grade. List the students down the left side and the Ramot numbers along the top. When a student completes a Ramah, mark the date in the appropriate square. This chart is for teacher and administrative purposes only and should not be displayed for students. Everything possible should be done to avoid a sense of competition among students.

A new tool for tracking student progress and facilitating student-teacher communication is the Mitkadem Daily Journal . This one-page journal is a way for students to report their daily progress to the teacher, who can then add comments and notes about work that needs to be done. The journal pages can be kept in the student’s working folder and, at the completion of each Ramah, can be discarded or filed in the student’s cumulative folder.

12. How can we use madrichim (student aides) and/or parent volunteers in the Mitkadem classroom?

Student aides and/or parent volunteers can play an important role in the administration of the Mitkadem program. Teachers can always use assistance during class sessions to keep students on track, answer questions, and mark contracts as students complete activities. Parents or teen aides who are knowledgeable in Hebrew can help students with activities, tutor reading, and even serve as testers. Inviting parents into the classroom increases their involvement in the school, allows them to see firsthand what’s happening in the school, and helps build a sense of community. Teen aides can serve as mentors for younger students, and the interaction between age groups can add to the sense of community in the school.

13. Can students stay in age groups even if they’re working on different Ramot?

Yes—in fact the self-paced nature of the Mitkadem program virtually ensures that students in any one classroom will be working on a range of different Ramot. The average student should complete three to five Ramot per school year (after Ramah 2), but some students will complete more and others will complete fewer. The classroom will be (and should be) a buzz of activity, with students involved in a variety of activities at any given time. Each will be engaged with material that is appropriate for him or her, progressing at his or her own pace. You may choose to bring the students together for an all-class activity during the last fifteen minutes or so of class time, or even for an entire session every so often, in order to maintain a sense of community in the classroom.

14. Does Mitkadem include a homework component? How can we incorporate homework if we wish to?

There is no homework component built into the Mitkadem program, however, some students may want or need to have home reinforcement of the work they are doing in the classroom. Parents can choose to purchase a duplicate of each Ramah for use at home. This duplicate packet should include all the pamphlets and answer sheets, plus a copy of the audio recording, for additional home study. Having a copy of this material at home also allows parents to see what their child is learning and provides an opportunity for parents to learn from the material themselves. Students will still need to complete all of the activities in any Ramah in the classroom, but the additional practice at home, especially reading practice and chanting along with the audio CD, is an excellent reinforcement of the classroom learning. For more on homework, see the Mitkadem Teacher’s Guide for Ramot 3 through 6 .

15. Why do some Hebrew words appear to be spelled incorrectly? For example, why is lailah spelled with a kamatz and not a patach ?

Those who teach Hebrew certainly know that it is a complex language, with rules about grammar and spelling that can be quite intricate. Certain words, such as lailah , sometimes appear in construct form when used in prayers, and this form requires different vocalization than when those same words appear in common usage—hence, the kamatz in the word lailah , rather than the patach used when the same word appears in literature or other written form. Other examples include the words d’var, yad, dor, and av . These words have been included in the milon with the same vocalization that appears in the prayer so that students are not confused by seeing the same words with different spellings.

16. How should the flashcards be used?

The Teacher’s Guide for each Ramah contains a master set of flashcards of the vocabulary words, roots, and prefixes and suffixes listed in the milon (dictionary). The set can be copied onto card stock, and each student can cut out his or her own set of flashcards. Flashcards can be used for simple drilling of vocabulary, for building a permanent milon , or for playing games such as concentration. More information about how to use flashcards is found in the Mitkadem Teacher’s Guides.

17. Can we ever have any all-class discussions or activities if we use Mitkadem ?

Definitely! In recognition of the importance of building community in the Hebrew school classroom, many schools use the last fifteen minutes or so of class time, or even an entire session every so often, to bring the students together for an all-class activity. It might be a discussion of the theological issues behind one of the prayers that students are currently studying; a game that reinforces vocabulary, grammar, or reading skills; or group singing in Hebrew. Some schools choose to begin a class session with a review of something that many students are confused by, or to look at t’filah thematically. A school using the CHAI Curriculum Core might incorporate material from the Avodah strand into Hebrew time as a way of bringing the class together. However they are used, these sessions are opportunities for teachers to contribute their personal creativity and knowledge to the classroom experience.

18. Can we make our own recordings?

Yes! The intent of the CD recordings is to help students become familiar with the prayers as they are read or chanted in the worship service. We recognize that each individual synagogue has particular prayer melodies that it typically uses, and those may be different from what is provided on the CDs. We encourage you to create recordings of the prayers as they are used in your congregation.

19. Our school would like to begin using Mitkadem . How do we transition from the Hebrew program we are currently using? How do we “place” students in the appropriate Ramah?

By now you understand that Mitkadem is quite different from other Hebrew programs. Therefore, it’s important to carefully think through how you will transition to Mitkadem from the Hebrew program you are currently using and to understand that the process will take some time. The order in which Mitkadem presents the prayers and blessings is different than other Hebrew programs, so you will need to compare, at each grade level, what material students have already learned against the Ramot structure. Many schools establish some general guidelines for progress through the Mitkadem program, a range of Ramot to be covered at each grade level (for example, you may set a goal of having all students in the fourth grade complete Ramah 8 before the end of the year). With such guidelines, you will have a general sense of where you would like students to be at any point in time (understanding, of course, that there will always be exceptions and special circumstances). Your decisions as to where to “place” students will need to take into account a balance between a desire to have students learn all the content provided by Mitkadem versus the need for students to progress at a certain pace.

In any case, it is very important that all students begin with Ramah 3. Ramah 3 provides an introduction to the structure of the Mitkadem program, and without this material students will be lost. Even students who already know many of the prayers will need to complete Ramah 3. From there, several different approaches are possible.

You may choose to have all students continue with the Ramot in order. It’s likely that even if students have already learned to read the prayer in a particular Ramah, they have not covered all of the grammar, vocabulary, and prayer words background that Mitkadem provides. You will need to decide if this material is important enough to spend your time on. In such a scenario, some students will move quickly through the next several Ramot while others will move more slowly, but over time each student will “settle in” to his or her appropriate level. The advantage to this approach is that all students will achieve maximum mastery of the prayers by completing all the material provided by Mitkadem . The disadvantage is that some students may feel as if they are moving backward to cover material related to prayers they have previously learned.

Another approach is to have all students complete Ramah 3 and then place each student into the lowest Ramah containing a prayer that he or she has not yet studied. You may wish to administer a reading test to help determine the appropriate level—more on this below.

Because many other programs do not cover the Kiddush (Ramah 5) and the Torah blessings (Ramah 6) until later, these Ramot are often a good place to begin. Use caution, however, and remember that the Ramot are designed to be completed in sequential order. It’s probably not a good idea to place a student in Ramah 9 without having completed Ramot 5 and 6 first. The advantage to this approach is that students will not need to go back and “redo” material they have already covered, a process that might put them behind your targets for completion. The disadvantage is that the level of prayer mastery for any Ramot that are skipped will not be as high as it would be had the student completed every Ramah.

The tests at the end of each Ramah can be used as “pretests” to pinpoint each student’s level of proficiency and guide what gaps in learning need to be filled. Be aware that testing can take a lot of time and that many students suffer from “test anxiety” and the results may not be entirely accurate. In addition, you will likely find that some students are able to read and chant a particular prayer, but because they have not had the vocabulary and grammar background that Mitkadem provides, they would not be able to pass the written test for that particular Ramah. Having them go back and master that material would take a significant amount of time and would set them behind the expected progress for their grade.

One director of a school using Mitkadem spoke about her experience with implementing the program in her school:

When we phased in Mitkadem in our older grades, we didn’t have students repeat prayers they already knew how to read and chant, even though it was clear they could not have passed the written tests. Our clergy were aware that the number of prayers this group would master before the end of grade 6 would be fewer than before as they learned to use the new system, but to go back and demand that they master the grammar and vocabulary and everything else would have really put them behind. It is always a balancing act between our commitment to the depth of content and our need for them to progress at a certain pace. We are reluctant to make modifications (i.e., only demanding reading and chanting proficiency) but sometimes we need to.

These are some of the decisions that you will need to make as you structure your school to use Mitkadem in the way that works best for you. There are no “one size fits all” solutions—the choices you make will be unique to your particular setting, taking into account a variety of factors and priorities. It is important that all of the stakeholders in your Hebrew program—school director, Hebrew coordinator, clergy, teachers, education committee, etc.—be involved in making these decisions. Please contact your URJ regional educator, who will be happy to help you with this process.

News Articles:

Ringing in Success with Mitkadem: An Up-Close Look at Making Independent Hebrew Learning WorkTeacher Tools:

Ramot Chart

A list of prayers per ramah as well as concepts introduced and reinforced.

Mitkadem Teacher Training

A lesson for educators to use to train their teachers about Mitkadem.

Mitkadem Implementation Guide

This guide will assist you in implementation of the Mitkadem program by providing you with wisdom from those who have been using the program, offering alternatives for implementation, and providing necessary information for both the administrator and teachers of the program.

My Goals for You

This form helps teachers communicate with each learner and set expectations for a period of learning.

I've Got a Question

This worksheet enables students to focus and articulate their questions without interrupting the teacher’s engagement with other children.

Classroom Update Form

Thank you to Tami Schoen for sharing this form

Free Fall Review Activities

These worksheets will help your students to review what they learned last year when they return to school this fall.

Ramah Postcards

Send these postcards home when a student completes a ramah. Thanks to Dennis Niekro for creating and sharing them!

Introducing Mitkadem to Families: A Family Education Program Outline

Developed by Kitty Wolf, this sample Family Education lesson can be used to introduce the Mitkadem program to parents and children.

Student Motivation Tools

- Mitkadem Daily Journal - a one-page daily journal for students and teachers to report on daily progress.

- Mitkadem Daily Brit - daily tracking and self-assessment on a short, single page

Audio for Ramah 6:

Record Sheets for Ramah 6:

The Mikadem Ramah Record Sheets are a great way to track the progress of your students!

Download the Mitkadem Program Cumulative Record sheet here.

Download the Mitkadem Program Cumulative Class Record sheet here.