How Can Art Spark Thinking and Learning?

By Elizabeth Diament, Senior Educator at the National Gallery of Art

By Elizabeth Diament, Senior Educator at the National Gallery of Art

Works of art by their very nature invite us to slow down, look carefully and wonder about them. When explored, using some simple yet powerful strategies, art can invoke higher order thinking. Works of art also have many stories to tell and visually connect students to a wide range of content areas.

So how can we create experiences with art images that strengthen students’ thinking and learning across the curriculum?

Since great works of art are layered and complex in their meanings, they have the capacity to inspire rich and creative thinking, helping students recognize multiple perspectives and generate probing questions about the art.

As a museum educator, I propose a model to integrate the use of art images into the school curriculum to foster creativity and independent thinking across disciplines. This model is based upon Harvard University’s Project Zero, a research-based organization that has developed a collection of thinking routines to activate patterns of thinking in K-12 students. Thinking routines are short sets of open-ended questions used primarily in a classroom environment to get students to draw on certain thinking skills such as reasoning, finding complexity, exploring viewpoints, and comparing, and connecting.

This teaching model, on some level, extends the art museum tour into the classroom. For example, in a Jewish school environment, great works of art can be used to compare and connect characters and scenes from the Bible with painted counterparts. For instance, Steenwijk,’s Esther and Mordecai from 1616, captures the clandestine and urgent meeting between Esther and Mordechai as they work to save the Jewish people.

At the National Gallery of Art, we have used thinking routines as effective tools to help both students and teachers develop their own reasoned interpretations of works of art. We found that thinking routines support both individual and group learning, giving each member of a learning group an opportunity to develop thoughts and ideas about an object, as well as structuring a conversation to promote dialogue within the group. When these thinking routines are used repeatedly, students begin to activate thinking dispositions independently, and in other curricula contexts.

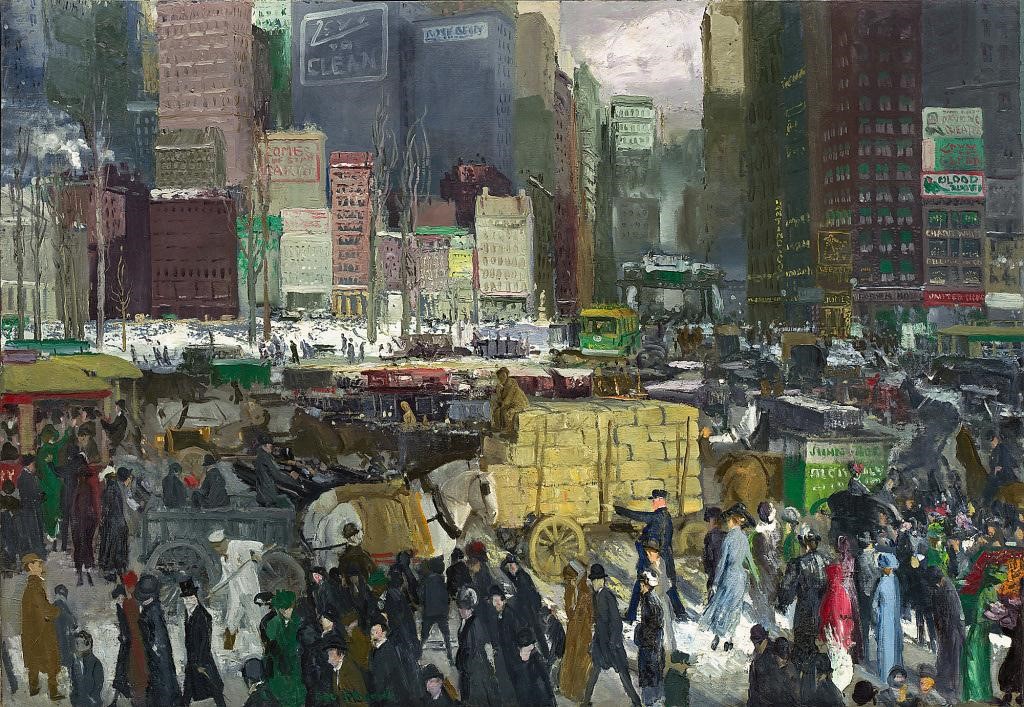

On a recent tour of 8th graders to the National Gallery, I used a routine called See/Think/Wonder that focuses on questioning, investigating, making inferences, and reasoning with evidence. We explored the painting New York, 1911 by the American artist George Bellows, and I invited the students to spend two minutes in quiet observation, letting their eyes wander across the surface of the work of art, and taking in as many details as possible.

New York, 1911. George Bellows (1882-1925), National Gallery of Art, Chester Dale Collection

See: Students jotted down words or phrases that described some of the aspects of the painting that they noticed. I encouraged them to try to focus on what they could purely see and not rush to interpretation. This initial visual inventory included: horses and carts, tall buildings, a crowd of people and a road sweeper. After sharing and comparing their observations with a partner, and then with the whole group, they returned to the painting and looked once again. This time their observations went deeper: I see a tramcar, bus and an old-fashioned horse and buggy. I see billboards on buildings. I see the snow and the bare trees. There is hardly any sky in the painting and the skyscrapers are blocking it. They discovered narrative elements and artistic choices. Through a mix of individual, small group, and whole group sharing, I was acutely aware that everybody’s idea had been heard and valued. There was an equity of engagement where everyone had a voice, which is an important outcome of this teaching model.

Think: Students were invited to take another look. I asked them: What do you think might be happening in this painting? Who do you think the people could be? My use of conditional language “might” and “could” invited many possibilities. Students shared: I think this could be a real place the artist had seen because the billboards seem to have identifiable words on them; People are rushing to their jobs because they look purposeful. Some of the people must be rich because I notice some top hats but some aren’t and don’t have a place to go to. It must be winter because the trees are bare and there is snow on the ground. The students’ ideas were enriched by their initial observations and they began to make inferences and connections based on evidence from the work of art. I encouraged the students to support their assertions with evidence from the painting. They were also listening to and responding to each other’s comments to, once again, build their thinking as a shared community.

Wonder: Students were invited to share and discuss in pairs their questions and wonderings, selecting one burning question to discuss as a group. They demonstrated signs of engagement such as returning to the painting and looking at it from different perspectives and pointing excitedly when they had an insight. They generated a broad range of questions and then chose one to share. I wonder if this is a real place that existed and these were real people? I wonder where they are all going? I wonder why there is a car, and a horse and buggy, in the same place? I wonder how it is I can almost hear the sounds of this place?

I provided an additional perspective on the choices the artist made in this painting, telling the students that George Bellows was part of a group of artists living in New York City who drew inspiration from the life they saw around them. Bellows said: “I paint New York because I live in it, and because the most essential thing for me is to paint the life about me, the things I feel today that are part of the life of today.” I also told them that Bellows deliberately added skyscrapers to the intersection of Broadway and 23rd Street in Madison Square, New York.

I strategically shared information to deepen inquiry, and not to provide the “right” answer, hoping to expand the conversation in new directions and provoke more questions and curiosities. I asked, “With this information in mind, what new things do you notice or what new questions and understandings do you have about this work of art?” The students raised an entirely new set of questions and the curiosity and engagement lingered. Why would the artist have included skyscrapers when they didn’t exist from this viewpoint? Should art be beautiful or truthful? I tossed the question back at them? Why do you think he would have made that decision to create a painting that was a document of reality but was really a composite, artificial image? What did Madison Square really look like at the time? I showed them a photo of Madison Square from the period. Their thinking and learning continued. The students had created collaborative ownership and understanding of a multifaceted work of art in a safe, non-judgmental space.

David Perkins, one of the principal researchers at Project Zero suggests “learning is a consequence of thinking. Retention, understanding, and the active use of knowledge can be brought about only by learning experiences in which learners think about, and think with, what they are learning.”

Whether an encounter with a work of art is a catalyst to inspire rich and imaginative writing or a lens into difficult moments in the Torah narrative such as the binding of Isaac, this teaching model can be used to nurture critical thinking skills across a broad range of classroom material. Thinking routines have the capacity to activate student’s deep thinking by privileging their own ideas as a valuable source of information, getting them personally involved, and using questions to drive learning and uncover complexity.

Elizabeth Diament is the Senior Educator at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Originally from London, she holds a degree in Art History from Manchester University and a Master’s in Museum Education from Bank Street College of Education. At the National Gallery, she manages school and adult tours and docent education for about 200 docents. Liz has been invited to lead professional development workshops in museum and school settings throughout the U.S. Inspired by her experience at the National Gallery, Liz has explored and presented about ways to integrate a museum teaching philosophy into the study of Torah and text.